|

| Arnold Ross at Saint Louis University in 1937 From Saint Louis University Yearbook |

In this post, I will continue talking about Arnold Ross and the support he provided African American students. In an earlier post, I talked about Arnold Ross and his involvement with African American student protests at The Ohio State University. The main account of this is a 2001 interview with Ross. In the same interview, Ross says that one of his students at Saint Louis University was the first black woman to receive an M.S. in mathematics in the South.

Saint Louis University is a private university in Missouri. Ross's description of Missouri as a Southern state can be debated. Missouri was a slave state until 1865 when state legislators outlawed the practice at a state convention. However, the state remained in the Union for the duration of the Civil War (although parts of the state strongly supported the Confederacy).

Southern or not, in the 1930s and 40s, Missouri was a Jim Crow state where blacks were denied equal access to amenities like housing, medical care, education, employment, and transportation by state law and local custom. Laws enforcing racial separation at universities did not apply to Saint Louis University because SLU is a private institution, but following local custom, the university excluded African Americans until 1944.

Ross gives a basic description of what happened in his interview:

Ross gives a basic description of what happened in his interview:

One of my students at St. Louis University was the first black woman to receive an M.S. in mathematics in the South. She was handicapped because she had had polio when she was young, and she was paralyzed in the left leg. The students and the young priests were with me in saying she should be accepted to the university, and that’s actually what made it possible for the university to make an exception and to start accepting black students when it was a very unpopular thing to do.

This account raises a number of questions. Who was the woman? How did people convince the university to admit her? (She was admitted a full decade before the Brown v. Board of Ed decision ruled the de jure segregation of public schools unconstitutional.) What was her experience at SLU like? What did she do after graduation?

Details about the desegregation of SLU are hard to find. There are a few accounts of the event, and the university has commemorated major anniversaries, but accounts focus on the efforts of (white) local priests to challenge segregationist policies. They mention that SLU ended its policy of racial exclusion at the start of the 1944 summer session when it admitted five African American students, but they don't even mention the names of all the students. I could figure out one name because the student showed up at commemoration ceremonies, but he was not Ross's student. (His degree, for example, was in education.) After doing some research, I found out that nobody seems to know the names. I reached out to Deborah Cribbs at the SLU Archives, and the university simply does not have any record of which students in the 1940s were African American.

Details about the desegregation of SLU are hard to find. There are a few accounts of the event, and the university has commemorated major anniversaries, but accounts focus on the efforts of (white) local priests to challenge segregationist policies. They mention that SLU ended its policy of racial exclusion at the start of the 1944 summer session when it admitted five African American students, but they don't even mention the names of all the students. I could figure out one name because the student showed up at commemoration ceremonies, but he was not Ross's student. (His degree, for example, was in education.) After doing some research, I found out that nobody seems to know the names. I reached out to Deborah Cribbs at the SLU Archives, and the university simply does not have any record of which students in the 1940s were African American.

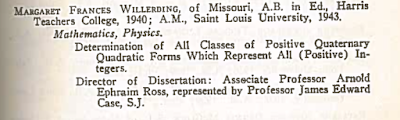

Despite the lack of records, I was able to figure out who Ross's student was using information that Cribbs provided. SLU regularly publishes a bulletin that contains basic educational information about each graduating masters and doctoral student. For example, here's the entry for Ross's student Margaret Willerding:

|

| Entry for Ross's student Margaret Willerding in the SLU Bulletin From the SLU Pius XII Memorial Library |

The published information includes the student's undergraduate institution. The early African American students can be identified from this because, due to segregation, they would have attended a historically black college or university (or, less likely, a university in the North that admitted African Americans). With this in mind, I was able to identify Ross's student. It was Margaret Cecil Gerdine Taylor.

|

| Photo of Margaret Cecil Gerdine Taylor From the 1941 Lincoln University Yearbook |

How do I know Taylor is the student? Here is her entry in the 1946 SLU Bulletin:

|

| Entry for Margaret Taylor in 1946 SLU Bulletin From the SLU Pius XII Memorial Library |

Lincoln University is a public HBCU in Missouri, so Taylor was African American. Moreover, while the entry doesn't list the name of her advisor, the topic of her master's thesis (binary quadratic forms) is on Ross's area of specialization.

The other possible students can also be eliminated. There were five women who received M.S. degrees in math from 1945 to 1946, and all but Taylor and one other student attended whites-only institutions. The other student was from Minnesota, received a joint math/physics degree, and wrote a thesis on experimental physics (title "Vapor Pressure of Liquid Bismuth by Two Methods Employing a Vacuum Microbalance") which is a topic Ross was unlikely to supervise.

|

| Photo of Margaret Cecil Gerdine Taylor From the 1942 Lincoln University Yearbook |

I was able to piece together a little bit of information about Margaret Taylor from historical records like census data. She was born in 1920 in St Louis to Clayburn and Lillian Gerdine. Both of her parents had moved to St Louis from Mississippi. The parents had probably moved to escape rural poverty and seek job opportunities in St Louis's then growing industries, a common pattern during the early 20th century. Her father worked as a laborer in the steel industry.

Taylor was from a large family. From the census data, it looks like she had 5 siblings. (It's a little unclear because it looks like 2 families were living in the same household, and some of Taylor's siblings may have died in infancy.)

Since Taylor attended SLU, the family was likely Catholic. While Mississippi had a small population of Catholics, it's likely that Taylor's family converted after moving to St Louis. The city had a large Catholic population, and the Catholic clergy were actively trying to convert new African American residents to Catholicism.

Taylor attended Lincoln University from 1938 to 1942. While there, she was a member of the Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, serving as Sorority Treasurer in 1942. She was also one of two students to receive a 1942 Student Council scholarship.

At Lincoln University, she had access to an excellent math education. Lincoln's faculty included Walter Richard Talbot, one of the first African American math PhDs (University of Pittsburgh 1935). At this time, few HBCUs employed PhD faculty in any field, and there were less than ten African American PhDs teaching mathematics in the entire country.

|

| Photo of Walter R. Taylor in 1938 From the 1938 Lincoln University Yearbook |

There is a 2 year gap between when Taylor graduated from Lincoln and when she entered SLU. She might have worked as a school teacher (one reference describes all the entering graduate students as public school teachers) and the change in last name indicates that she probably got married (she graduated from Lincoln as Margaret Gerdine but graduated from SLU as Margaret Taylor).

Taylor largely disappears from the historical record after she graduated from SLU. She died in 1993 and is buried in Calvary Cemetery. Calvary Cemetery is a Roman Catholic cemetery in St Louis, so presumably Taylor continued to live in the city and remained with the Catholic church for her adult life.

She is buried as Margaret T. Williams, and the Social Security records indicate that she had changed her last name by 1966. Presumably she became widowed in the 1960s (a Catholic divorce at the time would be very unusual) and remarried. Williams may have returned to teaching in the public schools after receiving her M.S. degree or she may have left the workforce to become a housewife or she could have done something completely different.

Somebody in St Louis with the time to dig deep into the St Louis archives might be able to find more information about Margaret Taylor. For example, one might be able to figure which school Taylor taught at. Taylor should show up in school records like yearbooks, and until 1954, there are a limited number of schools she could have taught at since she would have only been allowed to work at an blacks-only school. I couldn't find any digitized high school yearbooks, but local libraries and historical societies should have hard copies.

Taylor probably also has family still living in St Louis, and they might be able share more information. Many of her siblings stayed in the city and started their own families. Most of the siblings have probably died, but their children are likely in their 60s.

One might also be able to find information about Taylor in church records. In any case, there is certainly a lot more to do for someone in St Louis with time and interest. If any readers are able to track down more information, please let know!

(Additional posts on St. Louis University are "The desegregation of Saint Louis University and its mysteries" and "The Saint Louis University students.")

(Additional posts on St. Louis University are "The desegregation of Saint Louis University and its mysteries" and "The Saint Louis University students.")

No comments:

Post a Comment