|

| An artist's depiction of the Arkansas river as viewed from Little Rock. The view from Pine Bluff would have been similar |

|

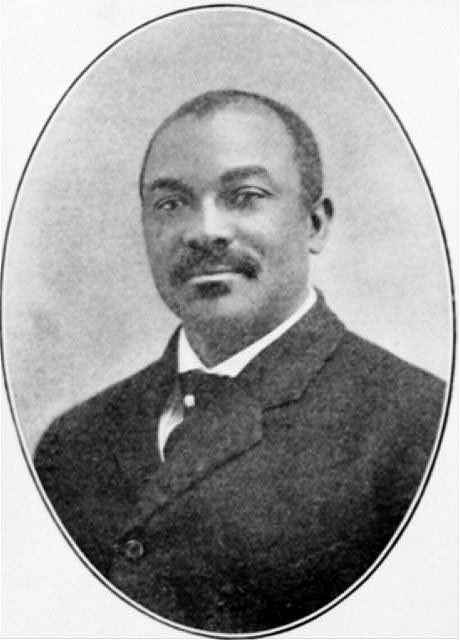

| J. C. Corbin From Wikipedia |

On September 27, 1875, visitors to Pine Bluff, Arkansas could witness a scene that they could well mistake for a malaria-induced hallucination. In the middle of this rough river town in the Arkansas Delta, a scholarly-looking Black man was welcoming students to a newly opened college. That man was J. C. Corbin, a forty-two year old graduate of Ohio University and the founding principal of the Branch Normal College, Arkansas's public Historically Black College.

The mere existence of the college was a remarkable achievement. The college had been created by the state legislature two years earlier. This was a time when the state government was dominated by a Republican Party that strongly supported Black Arkansans. Much had changed in the intervening two years. The Republican party had collapsed in chaos, and political power was gained by conservative Democrats that included the state's former slave-owning elite. The new government rolled back many of the changes enacted by Republicans, but it preserved some measures enacted to support newly freed slaves as a paternalistic gesture intended to "fuse" Black voters with conservative Democratic politicians.

The early history of the Branch Normal College is of interest because it represents an unusual road in the development of higher education for freed slaves. Most HBCUs founded during this era were founded by men with a background either in the military or in missionary work. Fisk University's founding president Erastus M. Cravath was a white pastor affiliated with the American Missionary Association. Howard University was founded by the Union general O. O. Howard. Booker T. Washington, the most famous African American educator of the nineteenth century, was neither a military officer nor a missionary, but he had been mentored by Samuel C. Armstrong, who was both the son of missionaries in Hawaii and a former Union general.

Pine Bluff during the nineteenth century

Pine Bluff was a natural place to provide services for freed persons as the town had become a regional center for Black life. The town is located in the south central part of the state, on the Arkansas river. The surrounding area is part of the Arkansas Delta. In the years before the Civil War, aspiring planters brought large numbers of enslaved workers to the area as the Delta offers superior conditions for cotton-growing.

Census records clearly tell the story of this growth. In 1850, there were just under six thousand people living in the county. Ten years later, at the outbreak of the Civil War, the population had more than doubled to just over fifteen thousand. Throughout this period, just under half (or approximately forty-five percent) of the population was enslaved.

As a river town, Pine Bluff played a central role in this growth. The most efficient mode of transport in southern Arkansas was along a river, so aspiring planters arrived in the town by boat and then, after establishing themselves in the countryside, sent their cotton there to be sold at market. The town grew even faster than the surrounding countryside: the population increased four-fold, from just under three-hundred residents to almost one-thousand four-hundred.

After the war broke out, the town's population swelled as freed slaves from the countryside went there seeking refuge. The town became a safe haven in fall 1863 when Union troops took control and set up a refugee camp. Soldiers remained there and even maintained an office of the Freedmen's Bureau until spring 1869. By 1870, Black residents represented nearly sixty-five percent of the town's population. This was a dramatic change. Before the war, they had been a substantial presence but never a majority.

The conditions that drew freedmen to the town also made it a challenging place to run a college. While Pine Bluff offered great economic opportunity before the war, it had never been an easy place to live. The town was subject to frequent flooding, and the climate was subtropical with hot humid summers. This made for an unhealthful, malarial environment that forced newcomers to go through a long and difficult period of enduring sickness while they acclimated.

The war, especially the large influx of refugees, strained Pine Bluff's meagre public infrastructure, so problems with sanitation worsened the already bad public health conditions. Disease ran rampant through the freedmen population, and mortality rates soared.

In the face of these considerable obstacles, Corbin had few resources to support the newly formed college. During the first years, the college was run out of a rented house that also served as Corbin's residence. He was the sole faculty member and was even responsible for menial tasks like cleaning the classrooms.

Skeptics would have questioned the value of providing Corbin with even this modest level of support. Slaves had largely been deprived of education, and Arkansas had only a negligible population of free persons of color. During the first few years after the war, the Freedman's Bureau and missionary societies had run schools for free slaves, but teachers focused on imparting basic skills like literacy rather preparing students for college. Corbin's own official reports on the college communicates a sense of frustration with the difficulties in recruiting and retaining qualified Black students. So, who were the students?

|

| Map of Pine Bluff in 1869. The location of the Branch Normal in 1875 is indicated in red. From Arkansas Digital Archive |

The first students at the Branch Normal College

The first class of students consisted of seven students drawn from Pine Bluff and Drew County (another county located in the delta). The students appear to have come from families of relative privilege. Consider the student Robert Allen. Robert was twenty years old and was living with his parents in Drew County. Robert was born in Arkansas, but his parents had moved from out-of-state (from North Carolina and Virginia). There's no record of Robert's family before the war, but they were almost certainly enslaved. (No free persons of color lived in Drew County in 1860). Robert's father was a wagon maker and a carpenter. These were skilled professions that put the family on firm economic ground and enabled the father to purchase real estate.

Also a member of the first college class was Angeline Vester. Angeline was thirteen years old, much younger than Robert, and had moved from out-of-state. She had been born in Louisiana and had moved to Drew County with her mother and stepfather. The stepfather was a Union veteran (formerly a private in the 98th Colored Infantry), and he likely brought the family to Arkansas to take advantage of the availability of farm land. By the time Angeline began her studies, the family was running a farm.

|

| Pine Bluff in 1908 The location of the Branch Normal College in 1883 is indicated by the light blue dot. From the Library of Congress |

The Branch Normal College in the 1880s

The college graduated its first student in 1882, seven years after it opened. A second student graduated the following year. Both students, James C. Smith and Alice A. Sizemore, remained at the Branch Normal to work as teachers, the first ones Corbin hired. Both were in their earlier twenties, so they had little direct experience with enslavement, but they had grown up around people who did. No information about Alice's background is available, but James seems to have come from a background similar to that of Robert Allen. James was born in Arkansas, but his parents had moved from out-of-state (from North Carolina, likely forcibly by an enslaver). His father worked as a carpenter and wheelwright.

The college moved to permanent facilities in January 1883. The new location was a modest one: a two-story brick building constructed on a twenty acre plot in the western outskirts of town. The college still offered no living facilities, so students continued to live off-campus in rented rooms.

|

| The Branch Normal College in 1908. Only the left-most building existed in 1883. The right-most building is a dormitory that was built in 1887. The building between them is a shop building constructed in 1893. From the Library of Congress |

The college celebrated its achievements at a June 1883 public ceremony held to mark the end of the academic term. The event was held off-campus at St. John's AME church. The nature of the event reveals a bit about how Corbin ran the college. The event opened with a prayer by Rev. Sylvester Hutchinson, likely the pastor at St. John's. This was followed by three student speeches: a salutatory (or welcome speech) on "Fame," a speech on "The Human Hand," and a graduating address by Alice A. Sizemore on "The Past." At the end, Frank J. Wise, a prominent white lawyer, presented diplomas. Music was played between the speeches. The first speech was preceded by the singing of the anthem and Hallelujah by the college choir. The "First Regimental March" was played next, following by "Spirit Creator of Mankind" by the Belgian composer Louis Lambillotte, and finally Gloria from Mozart's Twelfth Mass.

The song "First Regimental March" was likely the "Marching Song of the First Arkansas Colored Regiment." Singing this son was an act of major political significance. The song was written during the Civil War, and it is sung to the tune of "John Brown's Body." The lyrics proudly proclaim Black soldiers' opposition to the Confederacy. Some lines are "We are going out of slavery; we're bound for freedom's light; / We mean to show Jeff Davis how the Africans can fight" and "[Former enslavers] will have to bow their foreheads to their colored kith and kin." This was a remarkably bold act by students and faculty at a college funded by a state legislature dominated by former Confederate soldiers!

While not as blatant, the rest of the event also held political significance. The speeches displayed academic knowledge and were the types of speeches delivered by students at Predominantly White Institutions during the 19th century. When had graduated from Ohio University several decades earlier, Corbin had delivered a speech on "The Dangers of Literary Distinction." Compares these speeches to those delivered by students at HBCUs like Booker T. Washington's Tuskegee Institute. At a similar exercise held in 1882, the titles of Tuskegee student speeches included "Go to Work" and "The Drunkard's Daughter." The content of the speeches was not recorded, but the titles suggested that they were exhortations to avoid vices that whites alleged were prevalent among freedpersons.

Later that year, in December, the Branch Normal College held another public exhibit. At this event, students gave speeches displaying their knowledge of classical culture. One student delivered a declamation of Anthony's Oration over Caesar, while another gave one on "Rome." Other speeches emphasized students' connections to American culture. One student read a selection from George Washington's Inaugural Address, another spoke on "Revolutionary soldiers."

The music choices suggest similar attitudes. The songs played at the June event were taken from the European musical tradition. This ran counter to common expectations. In public music performances, especially those held for white audiences, students at HBCUs typically played music that came from (sometimes real, sometimes imagined) Black traditions such as spirituals.

A closer look at Branch Normal Students

We can get an unusually close look at Branch Normal students during the 1880s thanks to the work of an interviewer employed by the Works Progress Administration. In the 1930s, the WPA sponsored a project to interview freed slaves. Among those interviewed was Joseph Samuel Badgett, a former at the Branch Normal. Here's what Badgett told the interviewer about his experiences:

After that I went to Pine Bluff. The County Judge at that time had the right to name a student from each district. I was appointed and went up there in '82 and '83 from my district. It took about eight years to finish Branch Normal at that time. I stayed there two years. I roomed with old man John Young.

You couldn't go to school without paying unless you were sent by the Board. We lived in the country and I would go home in the winter and study in the summer. Professor J.C. Corbin was principal of the Pine Bluff Branch Normal at that time. Dr. A. H. Hill, Professor Booker, and quite a number of the people we consider distinguished were in school then. They finished, but I didn't. I had to go to my mother because she was ill. I don't claim to have no schooling at all.

John Young is listed in the 1893 college catalogue as living in Pine Bluff, but I can't find any other information about him. The other two people he mentions were deceased at the time of the interview, but they had been prominent educators and religious leaders.

|

| Former Branch Normal student A. H. Hill From "The Sons of Allen" |

A. H. Hill was Andrew Henry Hill. Hill was born after the war (in 1870) in Brentwood, Tennessee. I haven't been able to find much information about the parents, and in particular, it unclear if they were free or enslaved. When Hill was a child, the family moved to Monroe County and started a farm. When he was a young teenager, Hill became active in the AME church, but instead of immediately entering the ministry, he decided to enroll at the Branch Normal College. He completed his studies there in 1899 and then went to Ohio to attend Wilberforce University. He graduated the university three years later and then returned to Arkansas to serve as a minister at an AME church in Fort Smith. He also served president of Shorter College (an HBCU in Little Rock that is affiliated with the AME church) for almost a decade and was a minister in Pine Bluff.

|

| Joseph A. Booker From Encyclopedia of Arkansas |

Professor Booker was Joseph Albert Booker. His life before the war is relatively well documented. In 1859, Booker was born enslaved on a plantation near the modern town of Portland, Arkansas. The plantation was run by John P. Fisher, an early settler from New Hampshire. By the time Booker was born, Fisher's plantation was a sizable farm of 600 acres which was cultivated by fifty-five enslaved workers.

Booker experienced great hardship as a child. Both parents died when he was a baby. According to one account, his father was whipped to death for teaching other slaves to read. Booker remained on Fisher's plantation until after the Civil War. By 1870, he and his sister were working as farm laborer for a Black farmer (Jonia Georg).

|

| A modern photo of the Fisher plantation where Booker was born From Wikipedia |

Booker followed a path similar to that of Hill. He became interested in Christianity as a teenager (although he joined the Baptist church rather than the AME church) and enrolled at the Branch Normal College. The timeline of his studies is a little confused. Badgett says that Booker was at the school in 1882 or 1883, but accounts of Booker's life state that he attended from 1878 to 1881. In any case, at some point, he left the college and moved to Nashville, Tennessee in order to attend Roger Williams University, a now defunct HBCU founded by white abolitionists. He stayed at the university for five years, earning a bachelor's degree in 1886. Booker returned to Arkansas after completing his education. He served as minister for a church in southern Arkansas for year, and then he was elected president of Arkansas Baptist College, a HBCU in Little Rock. He remained in that position for the rest of his life.

Booker credited J. C. Corbin for instilling in him a deep love of learning while he was at the Branch Normal College, but politically, the two differed in important respects. Booker was a supporter of Booker T. Washington and even hosted him when he visited Arkansas. In keeping with Washington's views, Booker advocated a conservative political approach that emphasized accommodation over confrontation. In the 1900s, he served on a city vice commission charged with cleaning up Little Rock's red light districts, and he was appointed by the governor to a race relations committee created in response to a major 1919 race riot.

|

| Joseph A. Booker From AARG |

Joseph Samuel Badgett was not a major public figure like Booker or Hill, but his life is also well-documented. In his interview, he says that his mother was enslaved and "had Indian in her." The last statement is consistent with other public records which record her race as "mulatto." Joseph was born during the last year of the Civil War, so he was born into slavery but had no memory of being a slave.

Joseph says nothing about his father in his interview, and federal census records are contradictory about basic facts concerning him. The father is described as being born in Ohio in 1900 and 1910, but the 1940 census states he was born in Texas. One possibility for this silence and confusion is that the father was his enslaver, or another white man living in the household.

Joseph's enslaver was likely Madison Badgett, the only adult male with the last name "Badgett" who was recorded as living in the county in 1860. That year, Madison Badgett enslaved two women whose ages match the ages of Joseph's mother and older sister. No enslaved men were in the household, lending further support to the theory that Joseph's father was his enslaver.

After emancipation, Joseph's mother found work as a domestic servant, and he helped support her by working as a farmhand. Joseph was educated in the state's newly formed public schools, and his teachers included J. C. Smith. Smith was likely teaching between terms at the Branch Normal College to earn some extra income.

His WPA interview focuses on his early life, but Joseph achieved major personal success after leaving the college. He settled in Little Rock and worked as an upholster and then as a barber. At the time of his interview, he had owned his own home for decades.

The Branch Normal College changed significantly after Corbin left. His departure was part of a wave of changes throughout the south as populist politicians rose to political power and created the Jim Crow political system that sought to reduce Black citizens to a state of near-slavery. At the Branch Normal, Arkansas politicians worked to replace the college's academic coursework with training for semi-skilled professions. The campus environment during the 1920s was depicted by novelist Chester Himes (whose father had been on the faculty) in his autobiography and, in fictionalized form, in his novel The Third Generation. Himes depicts the Branch Normal as a wild place where the children of poor and ignorant sharecroppers learned to become "good farmers an' good blacksmiths an' good Nigras," in the words of the governor in The Third Generation. The learning of classical western culture that Corbin had promoted was entirely gone.

|

| Map of Pine Bluff in 1923. The location of the college is indicated in red. University of Arkansas Library |

No comments:

Post a Comment