In this post, I want to take a look at the 1876 election in South Carolina through the lens of statistics. The post will be riffing on Ronald F. King's article "Counting the Votes: South Carolina's Stolen Election of 1876."

The election was among the most eventful in American history. It resulted in white Conservatives sweeping the pro-Black Republican Party out of office. The state's electoral votes played a key role in Rutherford B. Hayes's presidential victory, and for generations, South Carolina would be governed by white Conservatives who almost wholly excluded Black people from political life.

The Conservative victory was all the more remarkable because demographics were against them. Politics were sharply divided along racial lines, and white voters made up only one-third of the electorate. How did their achieve victory? By "shoot[ing[ negroes to get relief from the galling tyranny to which we had been subjected," in the words of the influential politician Benjamin Tillman.

Political violence played two significant roles. First, it allowed the radical faction of the conservative party to dominate the party. In the summer before the election, the conservatives were divided between moderates who felt it best to accept Republican rule and extremists who wanted to try and throw out all Republicans. Going into the summer, it appeared that the moderate wing would prevail, but starting in July, radical Conservatives provoked several horrific violent political riots. This polarized politics so much that all moderation was abandoned.

The second role of political violence involved events after Election Day. The electoral outcome was close, and each candidate claimed to be the victor. The result was chaos. For almost a year, two different bodies claimed to be the state legislature, and a great deal of ink was split trying to resolve the issue through political and judicial procedures. Ultimately, the matter was decided not by pen and ink but rather by rifle and saber. Over the years, conservatives politician had organized a state-wide paramilitary group that was more than capable of overwhelming the state government's meager law enforcement and military forces. They were temporarily held back by the presence of the US army (the one organization capable of mustering greater armed manpower). However, in March, the president ordered the army to disengage from the political conflict. Continuing to press his claim would have put the Republican claimant's life in danger, so he finally conceded defeat.

The goal of this post is to closely examine the election returns. Conservatives leaders were only able to challenge the electoral outcome because the vote was so close. When the votes were counted, the Conservative candidate for governor was ahead by 1,324 votes. However, the returns from three counties, Barnwell, Edgefield, and Laurens, were challenged by Republicans who claimed that Conservatives had committed illegal ballot fraud and voter suppression. The ballot total with these three counties dropped was a victory for the Republican candidate.

The political process for resolving the dispute was completed and, ultimately, irrelevant. Under the state constitution, the newly elected state legislature was to declare the vote for the governor, but two different organized bodies claimed to be the legislature and each declared a different candidate the governor. While each body offered legal justifications for their decisions, the only argument that the Republican-dominated body ultimately found persuasive was that an armed paramilitary group would murder them if they continued to deny legitimacy to the Conservative-dominated body.

Here I want take a close look at the the actual votes using statistics. The election is particularly amenable to statistical analysis because the political and legal processes generated a create deal of data. Moreover, no statistics were done at the time, so we can hope to get new insight into what happened with this historic event.

The Statistics Analysis

There are three basic questions that I think are important to answer:

1) Were the ballot counts from the counties of Edgefield and Laurens legitimate?

2) What about the counts from other counties? Although Republicans ultimately accepted the counts for Barnwell County, they claimed that those elections results were improper as well. Conservatives charged that Republicans themselves had committed fraud, especially in the counties of Beaufort and Charleston. Do these results hold up?

3) What would the election outcome have been if there had been no election fraud?

Statistics alone can't answer these questions. Regarding the first question, a statistically unlikely voter count for Edgefield could represent voter fraud or it could represent unusual local political conditions.

In his paper, Ronald F. King uses a very simple but also very useful statistical model of the election. He assumes that race is the only determiner of voting behavior, and the each candidate gets fixed proportion of the white vote and the Black vote. These proportion can be estimated using statistical techniques.

A bit more formally, King's model is that

Y = p X_1 + q X_2,

where

Y = the proportion of the vote that Republican candidate gets

X_1 = the percentage of voters that are Black

X_2 = the percentage of voters that are white

p, q = are the fixed percentages of votes that the Republican candidate gets.

The quantities Y, X_1, X_2 are treated as random variables, and we treat each county as a sample of the random variables. Since X_1 + X_2 = 1, the previous equation can be rewritten as

Y = q + (p-q) X_1,

and King estimates p and q by a least squares linear regression on the county data. The Democratic candidate is handled analogously.

The model clearly has a number flaws. Voter behavior was certainly impacted by more characteristics than just race. For example, birth state played a huge role in determining the behavior of white voters. White men who were veterans of the Union army and had moved to South Carolina after the war were among the most loyal Republicans. The counties were also far from homogeneous. Almost everyone in South Carolina was a farmer, and in most part parts of the state, they grew mostly cotton and corn. However, in a few counties along the coast, rice was the main agricultural product. Despite these flaws, we will see that it works quite well.

There are five sets of data that we will use to make our statistical estimates:

1) the county-level election returns

2) a county-level record of election day sign-ins,

3) the 1870 federal census record of the populations of the counties

4) the 1880 federal census record of the populations of the counties

5) a 1875 state census of the population of the counties

Each of the data sets 2), 3), 4), and 5) can be used to estimate the percent of white residents / black residents.

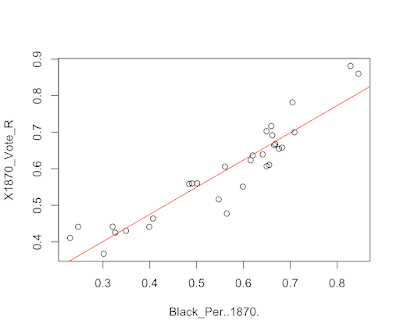

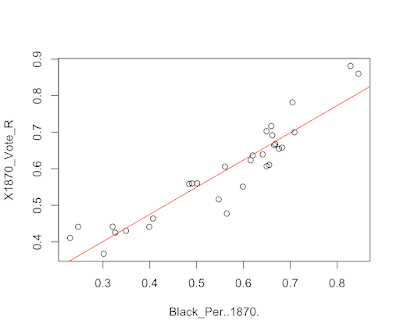

The plot below shows the data. Each data point is a county, the x-axis measures the percentage of the population that was recorded as "Black" in the 1870 census, and the y-axis measures the share of votes that went to the Republican candidate. Visually, we see that most points approximately lie on a straight line, but there are a few outliers.

The equation of the red line is Y = -.033 + .891 X. In other words, the least squares estimate is that the Republican candidate got -3.3% percent of the whites vote and 85.8% of the Black vote. Certainly the negative percent does not make logical sense and is an artifact of our statistical methods, but it indicates that the share of the white vote was negligible. The 85.8% figure is also reasonable. Historical accounts report widespread dissatisfaction with the Republican party, and some Black voters turned to the Democratic party either out of opportunism or after being physically threatened.The adjusted R-squared value is 0.857, confirming that a linear model is a good fit for the data. The standard errors for the constant term -.033 and the linear coefficient .891 are .0348 and .0663 respectively. The 95% confidence interval for the constant term is (-0.111, 0.046); for the coefficient, it is (0.755, 1.026).

Our estimates differ from those reported by King in his paper because we are using different data. Instead of using the 1870 census, King used two different models, one based a 1875 census and one on a record of voter sign-ins. A second difference is that I am assuming all eligible voters cast ballots, but King's model allows that some voters do not.

Despite the differences, the models are broadly consistent. For example, using the 1875 census (and dropping Charleston County) King gets the linear model Y = -.033 X + .946 X. The constant term of this equation and the constant term I got are the same up to rounding error. The linear coefficients differ but by a quantity that is approximately .83 standard errors.

Predicting a Fair 1876 Election

Now that we have the statistical model, what can we say about the ballot counts in Laurens and Edgefield? The plot below is a plot of residuals, that is the difference between the actual value of Y and the value predicted by the model. If the linear model is a good fit to our data, we should expect the data points to be clustered around the x-axis but otherwise not display any discernible pattern. This isn't quite what we see. Three counties are flagged for having unusual values. These are the data points labeled "3", "4", and "12." They correspond to the counties of Anderson, Barnwell, and Edgefield. Just as Republicans claimed, the votes for Republican candidate in Barnwell and Edgefield are suspiciously low. The returns from Anderson County were not challenged, but it isn't surprising to see the county appear as it shares many characteristics with Edgefield (both are in the northwestern part of the state and lie on the Georgia border), so it wouldn't be surprising if there were voter suppression efforts and ballot fraud there.

The statistics don't flag the counties of Beaufort and Charleston although some Conservatives claimed that Republicans living there engaged in voter fraud. Laurens also doesn't appear, but the voter returns look suspicious for other reasons. The reported number of Republican votes precisely matches the recorded number of Black voters and similarly with the Conservative votes. Presumably, the election managers didn't actually record the number of Black voters and instead just assumed that they all voter Republican.

What about the votes for the Conservative candidate? In our model, everyone votes, so the vote share that goes to Conservative candidate is 1-Y. In particular, we do not get more information by looking at the Conservative votes.

What should the election outcome have been? We can answer this question by using the linear model to estimate what the votes in Edgefield, Barnwell, and Anderson should have been. The table below shows what we get:

|

County |

Actual Republican Vote |

Predicted Republican Vote |

95% Confidence interval, lower bound |

95% Confidence interval, upper bound |

|

Anderson |

21.29% |

32.25% |

19.75% |

44.76% |

|

Barnwell |

41.25% |

51.94% |

39.59% |

64.29% |

|

Edgefield |

33.14% |

50.04% |

37.71% |

62.38% |

We can only reject the Edgefield result at the 95% confidence level, but Anderson and Barnwell are close. The table below shows what the votes predicted by the model are:

|

|

Actual |

Predicted |

|

Anderson County, Republican Vote |

1124 |

1702.48 |

|

Barnwell County, Republican Vote |

2778 |

3497.64 |

|

Edgefield County, Republican Vote |

3107 |

4690.75 |

The differences in these three counties are significant enough to have changed the election. The numbers are displayed in the table below. If voter fraud in Edgefield had been prevented, Republicans would have won the election. Our numbers differ from those in King's article, but the general conclusion is the same: in a fair election, the Republican wins by a few thousand votes.

|

|

Republican |

Conservative |

Republican – Conservative |

|

Reported Votes |

91,127 (49.69%) |

92,261 (50.31%) |

-1,134 |

|

Votes with Edgefield replaced |

92,711 (50.55%) |

90,677 (49.45%) |

2,034 |

|

Votes with Edgefield, Barnwell, Anderson replaced |

94,009 (51.26%) |

89,379 (48.73%) |

4,630 |

While a statistical analysis shows that the Republican party should have won the election, it also shows that the Republican Party was in serious trouble. The Republican Party had won the previous election by a comfortable 11,585 votes.

The Other Elections

The unusual nature of the 1876 election shows up even more clearly if analyze the earlier elections. Plots of Black population versus Republican voter share for the elections in 1874, 1872, and 1870 are shown below. For the years 1874 and 1872, there is a clear correlation between voting behavior and the Republican voter share, but it is weaker than it was in 1876. Another notable point is that the linear models predict that Republicans pick up a significant share of the white vote, more than one-third in 1874. These features can be explained by the nature of the elections. There was not really a Conservative gubernatorial candidate. Instead, the two main candidates represented opposing factions within the Republican Party. The candidate labeled as "Republican" was the regular Republican who ran against a Reform Republican. Conservatives endorsed the Reform Republican in 1874, but they ignored the gubernatorial race and focused on the presidential election.

|

| The 1874 election |

|

| The 1872 election |

|

The predicted large white vote for the Republican candidate might be an artifact of the model we are using. The model does not account for voters not casting a ballot, and I speculate that many white voters stayed at home on the election day in 1874 and 1872.

A glance at the 1874 election showed the presence of three outliers. Three counties had large Black majorities but very few people voted for the Republican candidate. The counties are Charleston, Sumter, and Clarendon. I was surprised to see them showing up because I haven't encountered any discussion of these highly unusual outcomes. I checked the outcomes, and there do not appear to have been any accusations of fraud or misconduct, and certainly, Conservative newspapers would have crowed about any reports their received. One possible explanation of the outliers is local politics. The outgoing governor, Franklin J. Moses, was from Sumter County. Moses is regarded as a disaster as governor, and he was one of the most hated in the state. The Republican candidate was an outspoken enemy of Moses, and low votes in Charleston, Sumter, and Clarendon may indicate that Moses had retained a loyal base in those counties. Moses was from Sumter, and the county shared a border with Clarendon.

Of the three elections, the 1870 election shows the strongest correlation between race and voter. The adjusted R-squared value is 0.8625, approximately the same as in the 1876 election. This is consistent with the historical record. The year 1870 was a year in which Conservative played an active role in state elections. They formed a "fusion" ticket with moderate Republicans and ran under the name of the "Union Reform" party. The Union Reform candidate for governor was a moderate Republican, but the candidate for lieutenant governor was M. C. Butler, a former Confederate general from Edgefield who played a central role in the 1876 election.

|

| The 1870 election |

An inspection of the residuals suggests that, unlike the 1876 election, a linear model is not the best one to use for the 1870 election. The residual plot is displayed below. You'll see that the residuals do not appear to be uniformly distributed near the x-axis. Instead, their plot appears to approximate a concave up function. This typically suggests that a non-linear model is a better fix for the data, and a pattern to the residuals disappears if we instead us instead use the quadratic model

Y = q + (p-q) X_1 + r X_1^2.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment